Rationalism—Socrates-Plato, Descartes, Spinoza, the Enlightenment (Part 2)

A Biblical critique of the rationalism of Socrates-Plato

Rationalism—Socrates-Plato, Descartes, Spinoza, the Enlightenment (Part 2)

Socrates (ca. 470-399 B.C.)-Plato (ca. 428-348 B.C.)

“With reference to the origin of the pure concepts of reason, and whether they are derived from experience, or have their origin independent of experience, in reason. Aristotle may be considered as the head of the empiricists, Plato as that of the noologists [rationalists].”5

It is difficult, if not impossible, to differentiate between the teachings of Socrates and Plato because Plato recorded the teachings of Socrates and named the main speaker in his writings as “Socrates.” There are different theories of where the teachings of one ends and the other begins, however, for all intents and purposes, their teachings have come down to us as one body of literature.

Plato’s writings on the soul were in his works Phaedo and Meno, his most famous political work is The Republic, and his difficulties and problems in his philosophy were acknowledged in Parmenides.

Socrates-Plato may be called idealists because of their commitment to find a certain basis for absolute truth in ethics and reality.

Socrates, as recorded by Plato, defended absolute truth against the Sophists who were relativists.6

Socrates-Plato also sought to defend absolute truth and ethical absolutes in the context of political and cultural upheaval after the Peloponnesian War (431-404 B.C.), the philosophy of Heraclitus (490-420 B.C.) who taught that reality was ever-changing (“flux”),7 the philosophy of Democritus (460-370 B.C.) who taught the materialistic philosophy of atomism (that all reality is physical material made up of atoms). Socrates-Plato also dealt with the superstitions of Greek religion. These philosophies threatened reason, knowledge of objective reality, and ethical absolutes.

Socrates—The Wisest Man on Earth

Socrates championed the use of man’s autonomous reason in the search for truth. Socrates believed in the possibility of neutral objectivity in human reason. For Socrates, all of life and every thought should be brought under the lordship of man’s reason (cp. 2 Corinthians 10:5). Socrates-Plato put reason above sense experience (empiricism) and rejected relativism and skepticism. Absolute truth and certainty could be realized through reason.

“For I, O Athenians! have acquired this character through nothing else than a certain wisdom. Of what kind, then, is this wisdom? Perhaps it is merely human wisdom. For in this, in truth, I appear to be wise.... But, O Athenians! do not cry out against me, even though I should seem to you to speak somewhat arrogantly. For the account which I am going to give you is not my own; but I shall refer to an authority whom you will deem worthy of credit. For I shall adduce to you the god at Delphi as a witness of my wisdom, if I have any, and of what it is. You doubtless know Chærepho: he was my associate from youth, and the associate of most of you; he accompanied you in your late exile, and returned with you. You know, then, what kind of a man Chærepho was, how earnest in whatever he undertook. Having once gone to Delphi, he ventured to make the following inquiry of the oracle...for he asked if there was any one wiser than I. The Pythian thereupon answered that there was not one wiser;...”8 (emphasis added)

How did Socrates think he was the wisest man on earth?

“In this trifling particular, then, I appear to be wiser than he, because I do not fancy I know what I do not know.”9

Somewhat ironically, Socrates sought to prove or disprove the oracle that he was the wisest man on earth, not through reason, but through testing the proposition.

In Socratic reasoning, there were two main tools—dialectic (defining terms, critical question-asking) and introspection (internal self-reflection).

“Dear Crito, your zeal is invaluable, if a right one; but if wrong, the greater the zeal the greater the evil; and therefore we ought to consider whether these things shall be done or not. For I am and always have been one of those natures who must be guided by reason, whatever the reason may be which upon reflection appears to me to be the best;…”10 (emphasis added)

“Know thyself” (Philebus 48c)

Socrates was finally put on trial and executed in Athens for accusations concerning his philosophy. Socrates believed that he had a God-given mandate to teach philosophy and, therefore, would never stop studying philosophy.

“O Athenians! I honor and love you; but I shall obey God rather than you [cf. Acts 5:29]; and so long as I breathe and am able, I shall not cease studying philosophy,…”11

“For be well assured, this the deity commands. And I think that no greater good has ever befallen you in the city than my zeal for the service of the god.”12

Three characteristics of knowledge in Socrates:

Eternal forms/ideas (timeless, unchangeable, absolute)

Perception is an inadequate source of knowledge (The world is in continual flux, change, alteration, etc., therefore, knowledge must be independent of change)

Knowledge must be justified (cf. Symposium 202a)

Plato was influenced by the philosophy of Pythagoras (580-500 B.C.) who taught that all reality was made up of numbers and geometric shapes. According to this philosophy, this provided a fundamental orderliness to the universe which would be the basis for Plato’s argument about the world of Forms/Ideas.

Plato declared that the tangible (physical world of matter) was not as real as the real or true world of timeless, absolute, and unchangeable forms or ideas.

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave (Book VII of The Republic)

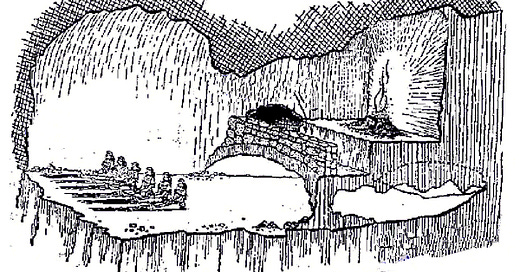

In an attempt to explain the nature of reality and distinguish between the reality of this world and the higher reality of ideas or forms, Plato delivered the well-known analogy of prisoners in a cave seeing shadows on a wall rather than the reality of what the shadow represents or the reality of the light of the sun.

“And now, I said, let me show in a figure how far our nature is enlightened or unenlightened: —Behold! human beings living in a underground den, which has a mouth open towards the light and reaching all along the den; here they have been from their childhood, and have their legs and necks chained so that they cannot move, and can only see before them, being prevented by the chains from turning round their heads. Above and behind them a fire is blazing at a distance, and between the fire and the prisoners there is a raised way; and you will see, if you look, a low wall built along the way, like the screen which marionette players have in front of them, over which they show the puppets....

And do you see, I said, men passing along the wall carrying all sorts of vessels, and statues and figures of animals made of wood and stone and various materials, which appear over the wall? Some of them are talking, others silent....

Like ourselves, I replied; and they see only their own shadows, or the shadows of one another, which the fire throws on the opposite wall of the cave?...

And of the objects which are being carried in like manner they would only see the shadows?...”13

Circular reasoning/Question-begging (Proverbs 26:4-5)

How was one to use reason to know the world of forms/ideas?

Socrates sought to come to a knowledge of reality through reasoning by dialectic and introspection but, in doing so, transitioned the basis for objective truth to the subjective-personal internal thought of individuals.

The forms/ideas are theoretical constructs that could not be known through empirical experience.

Plato also declared that we could, through reason, remember our preexistence in the world of forms/ideas. But to remember is to experience!

How do we know the unchanging, immaterial ideal? According to Plato, we look within (subjective) and remember what we experienced in this realm before we were born (sense experience). Thus, Plato must abandon his ultimate standard (reason) in order to establish it.

Job 38:1-7—“Then the LORD answered Job out of the whirlwind and said,

2‘Who is this that darkens counsel

By words without knowledge?

3Now gird up your loins like a man,

And I will ask you, and you instruct Me!

4Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth?

Tell Me, if you have understanding,

5Who set its measurements? Since you know.

Or who stretched the line on it?

6On what were its bases sunk?

Or who laid its cornerstone,

7When the morning stars sang together

And all the sons of God shouted for joy?”

Plato declared that the tangible (physical world of matter) was not as real as the real or true world of timeless, absolute, and unchangeable forms or ideas. But how could temporal and changing forms in the physical world be represented by timeless, unchanging, and absolute forms?

Plato incorporates rationalism (Forms) and irrationalism (sense experience). For Plato, reason is competent for his imaginary world of Forms but incompetent in the changing world of experience.

Biblical reason is competent yet limited. This means the changing world is knowable because of the standard of the God who does not change (Malachi 3:4; Psalm 102; etc.) who knows all things exhaustively.

“Now to discover the Maker and Father of this Universe were a task indeed; and having discovered Him, to declare Him unto all men were a thing impossible.”14 (cf. Acts 17:23)

Plato admitted that there was a sovereign and transcendent Creator of all things but simultaneously declared that it was impossible to know Him to speak meaningfully about Him. In rejecting the universal general revelation of God given to man (cf. Romans 1:19, etc.), Plato was led to declare the existence of God while also rejecting His authority. He tried to establish the authority of reason through imaginary speculation. This led Plato to a worldview of absurdity that could not account for absolute truth by the use of reason. Plato lost the very thing he wished to affirm and defend because he rejected a Biblical worldview based in the true knowledge of God as the Creator.

Footnotes/Further Resources:

[5] Immanual Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. F. Max Muller, (New York, NY.: The MacMillan Company, 1922, second edition), pp. 684-685, Online version

[6] The pre-Socratic Sophist philosopher Protagoras is known for the quote, “Man is the measure of all things...” (80B1 DK). Plato interpreted this as a statement against objective truth. See also Bonazzi, Mauro, "Protagoras", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/protagoras/>.

[7] Heraclitus is known for the quote, “You could not step twice in the same rivers; for other waters are ever flowing on to you.” He also said, “There is nothing permanent except change.”

[8] Socrates, The Trial and Death of Socrates, 5, Online version

[9] Socrates, The Trial and Death of Socrates, 6, Online version

[10] Socrates, as quoted in Plato, Crito, Online version

[11] Socrates, The Trial and Death of Socrates, 17, Online version

[12] Ibid.

[13] Plato, “The Allegory of the Cave,” Book VII of The Republic, Online version

[14] Plato, Timaeus 28c

Applied Apologetics - Biblical/Christian Philosophy (YouTube Playlist)

Rationalism - Socrates-Plato, Descartes, Spinoza, the Enlightenment (Part 1) (YouTube)

Rationalism - Socrates-Plato, Descartes, Spinoza, the Enlightenment (Part 2) (YouTube)